The Great Chicago Fire

How a city rose from the ashes and changed fire codes for the better

On October 8th, 1871 the city of Chicago was devoured by one of the worst fires in U.S. history. At the time, the city boasted a population of nearly 30,000, a figure that would triple a decade later. Chicago had come a long way from the small settlement it once was in the early 1800s, owing it’s bustling metropolis reputation to the canals and cheap transportation that allowed for booming commerce and travel. Chicago was no stranger to fires, as the city’s infrastructure was mostly composed of wooden buildings and sidewalks.

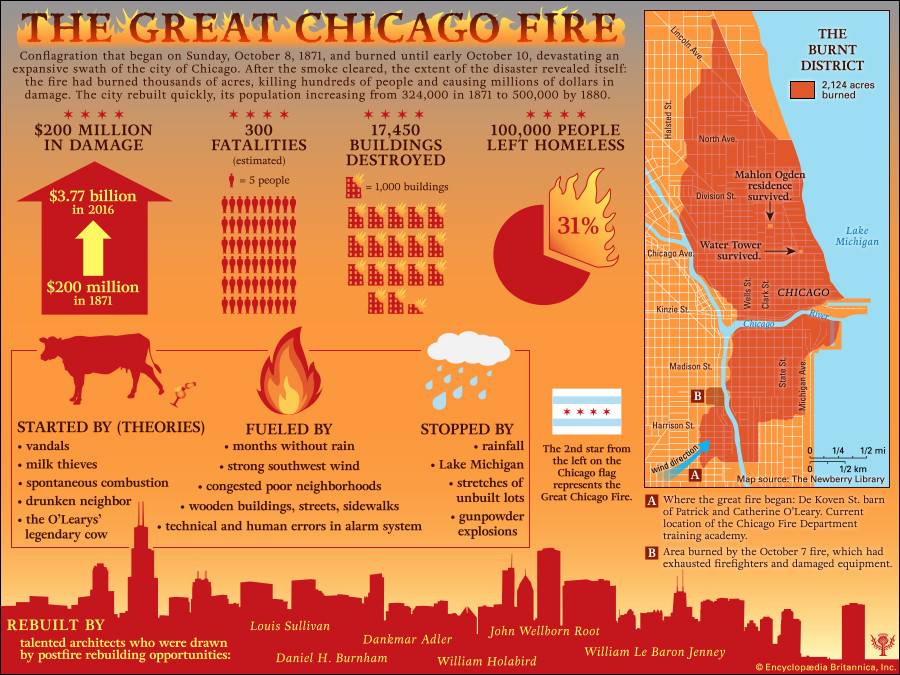

The fire, which would later destroy 2,124 acres, 17,450 buildings, cause $200 million in property damage, and kill 300 people, all began in the O’Leary’s barn on the West Side. The fire soon began to encroach northward, carried by steady winds, feeding off the wooden buildings, growing in the bowels of the city’s slums.

The Great Chicago Fire would rage for 2 entire days, eventually extinguishing on the morning of October 10th, 1871. The fire was bested by rainfall, Lake Michigan, and the stretches of empty lots that starved the hungry flames.

Chicago rose out of the ashes from the Great Fire with the assistance of talented architects and a newly elected mayor, who enacted stricter fire codes (a pledge said to help him win office just a month after the disaster, or perhaps the voting records were destroyed by the fire, thus citizens could have voted more than once). In 1893, Chicago hosted the legendary World’s Columbian Exposition—an attraction visited by 27.5 million people. Not bad for a city that burned to the ground 30 odd years prior.

The cause of the fire remains unknown to this day. Theories suggest milk thieves, drunken vandals, or even the O’Leary’s cow kicking over a lantern. Today, the O’Leary’s barn–the site of the fire’s origin–is now home to the Chicago Fire Department training academy.